An Intro To Sake Categories

Sake is an awesome, delicious drink with lots of tradition and education behind it. From its brewing process, to its different categories, to the specific ways and occasions in which people drink it, there is plenty of information about sake out there, and this may result very overwhelming for people who are just getting acquainted with it.

If you wanted to become a sake samurai, you would have to go to sake school. But for now, if you just want to start with some basics that will help you understand the most important aspects of this unique drink, here are some key concepts and terms we hope you’ll find useful .

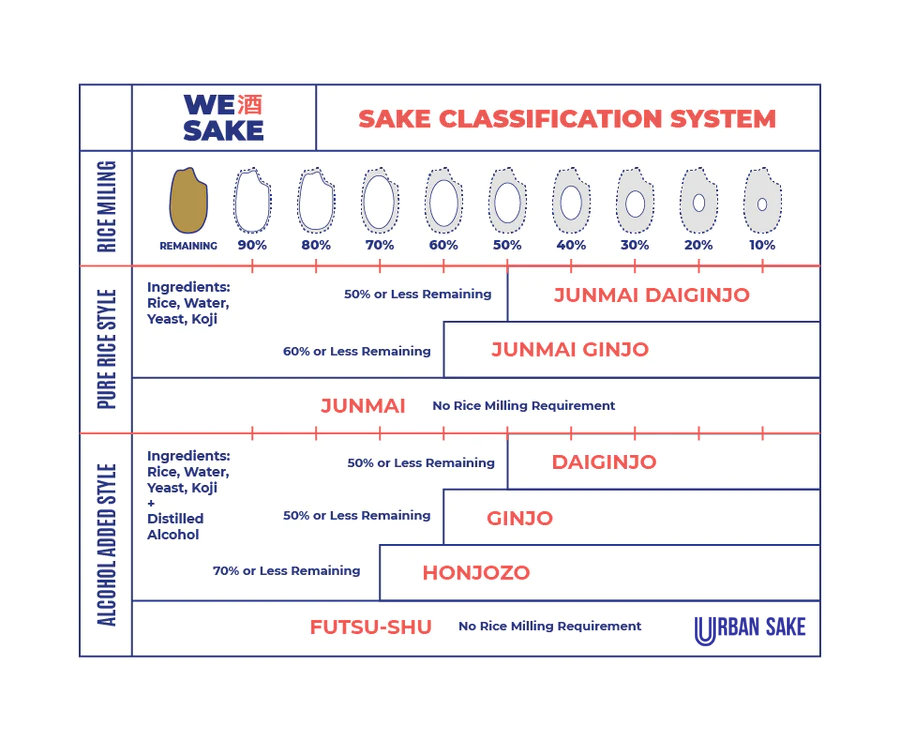

Polishing

One of the first steps in sake making is the polishing of rice. What does this mean? That the rice kernel has to be “polished” — or milled — to remove the outer layer of each and every single grain, so its starchy core is exposed. A useful example is imagining that to go from brown rice to white rice, you need to polish each grain to about 90 percent (i.e., polishing off 10 percent).

Now, in order produce good sake, you need to polish off much more than that! We’ll get into a little more detail below...but for now, keep in mind that good sake is usually polished to about 50 to 70 percent (i.e., polishing off anywhere from 30 to 50 percent). So if you read that a sake has been polished to 60 percent, it means 40 percent of the original rice kernel has been polished away, leaving it at just 60 percent of its original size.

So what is the point in losing a huge percent of each grain? That the more rice has been polished, the higher its classification level. Just keep in mind... more polished rice doesn’t necessarily mean better rice: sake experts also love the cheaper local stuff, as long as it’s made by good brewers from quality ingredients. Ultimately, you should trust your own palate and preferences.

Sake Categories

Just as with many other drinks, sake can be classified into different types according to the way they are brewed and the percentage of milling used in each brewing process.The variation in these conditions will give each type of sake a very unique flavor, scent and overall drinking experience.

The five main kinds of sake are: Junmai, Ginjo, Daiginjo, Honjozo and Namazake. Let´s dive a little deeper into each one...

Junmai

The word Junmai literally means "Pure Rice" so it refers to pure rice (non-additive) sake. Additionally, the Junmai classification means that the rice used has been polished to at least 70 percent. While it’s hard to over-generalize, Junmai sake tends to have a rich full body with an intense, slightly acidic flavor. This type of sake can be particularly nice when served warm or at room temperature.

Honjozo

Honjozo also uses rice that has been polished to at least 70 percent (as with junmai). However, Honjozo, by definition, contains a small amount of distilled brewers alcohol, which is added to smooth out the flavor and aroma of the sake. Honjozo sakes are often light and easy to drink, and can be enjoyed both warm or chilled.

Ginjo and Junmai Ginjo

Ginjo is premium sake that uses rice that has been polished to at least 60 percent. It is brewed using special yeast and fermentation techniques. The result is often a light, fruity, and complex flavor that is usually quite fragrant. It’s easy to drink and often (though certainly not as a rule) served chilled. Junmai Ginjo is simply Ginjo sake that also fits the “pure rice” (no additives) definition.

Daiginjo and Junmai Daiginjo

Daiginjo is super premium sake (hence the “dai,” or “big”) and is regarded by many as the pinnacle of the brewer’s art. It requires precise brewing methods and uses rice that has been polished all the way down to at least 50 percent. Daiginjo sakes are often relatively pricey and are usually served chilled to bring out their nice light, complex flavors and aromas. Junmai Daiginjo is simply Daiginjo sake that also fits the “pure rice” (no additives) definition.

Futsushu

Futsushu is sometimes referred to as table sake. The rice has barely been polished (somewhere between 70 and 93 percent), and — while we’re definitely not qualified to be sake snobs — is the only stuff we would probably recommend staying away from. Surprisingly, you can get really good-quality sake for very reasonable prices, so unless you’re looking for a bad hangover (and not-so-special flavor), stay away from Futsushu.

Nama-zake

Most sake is pasteurized twice: once just after brewing, and once more before shipping. Nama-zake is unique in that it is unpasteurized, and as such, it has to be refrigerated to be kept fresh. While it of course also depends on other factors, it often has a fresh, fruity flavor with a sweet aroma.

Nigori

Nigori sake is cloudy white and coarsely filtered with very small bits of rice floating around in it. It’s usually sweet and creamy, and can range from silky smooth to thick and chunky. This type of sake seems to be far more popular in Japanese restaurants outside of Japan than in Japan.